#KoiKoiUG panel at Writivism 2017 in Kampala. Photo credit: Andrew Pacutho.

#KoiKoiUG panel at Writivism 2017 in Kampala. Photo credit: Andrew Pacutho. Ok, I think it’s about time for me to write about White Privilege in the context of Uganda. A little self reflection – and you don’t have to go deep – brought me to the conclusion that I am experiencing a lot more privileges than my Ugandan friends in their own country.

I don’t like the word “expat,” because Ugandans in Toronto are not called expats – they’re called “immigrants” - and also it sounds too close to “expert.” We cannot deny that many white people in Uganda are paid more than their Ugandan colleagues, regardless of some migrants' inferior expertise in their roles and responsibilities.

On many occurrences, I have been waved through security checks while the Ugandan people I’m with are asked to open their bags. I actually have to say: “here, check mine too.” I often joke cynically that the biggest terrorist threat in Uganda could be a muzungu’s purse.

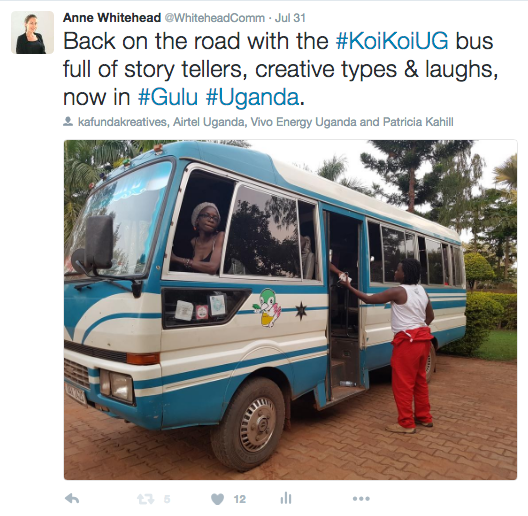

I have traveled a lot with my Ugandan friends around the country, and I have one friend named Nvannungi who likes to tease me with the reminder: “Anne, your White Privilege is showing!” (This blog is dedicated to you, Leadership.)

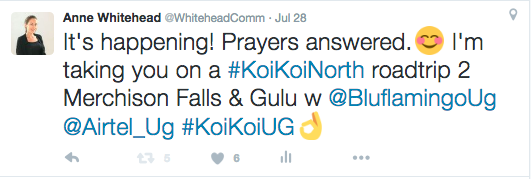

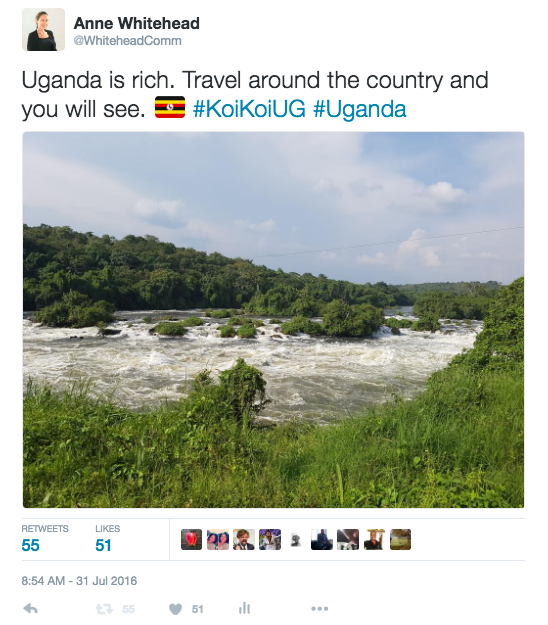

Last year, I travelled upcountry with my housemate Zalwango, and we noticed that many of the hotel staff and other service providers would look me in the eye while speaking, and pretty much ignore her. They’d offer to carry my bags and not even notice when she held out hers. I tweeted about this and was advised that I was served better in the expectation of better tips - muzungu = $$$ - never mind the reality of the situation, which was that my friend and I were splitting the cost of the trip and deserved equal service. We were both upset, not at the people themselves, but at the injustice in that way of thinking.

I have worked on so many funding proposals and pitches of different kinds with teams of Ugandans, and we noticed that when a Ugandan teammate contacts a potential partner, they are often ignored, but the name Whitehead gets a reply. I understand the lack of trust in a market that can often be too “unserious” about professionalism and integrity, and I do good work, but my muzungu name also has a more positive prejudice.

When a Ugandan welcomes a muzungu into their country, they open doors (literally and figuratively) lead you in and offer you the best seat available. They are warm and receptive. They take time to talk with you, and offer you any food or drink they have. A Ugandan will speak their very best English with a muzungu, and then praise the migrant for even one or two words in the local language that they can fumble out. A Ugandan does not expect a foreigner to learn their languages the way a Ugandan would be expected to speak English in America.

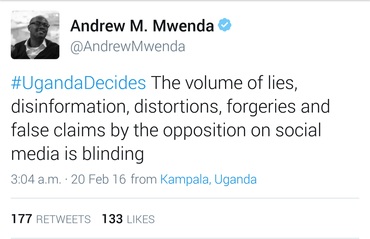

Through a confluence of a trending news cycle and my relationships in Uganda’s media – and I think some White Privilege – I found myself this past week in the middle of a story that run faster than Kiprotich. Everyone was giving me credit for PR that I wasn’t doing, calling me a “manager” of someone I wasn’t even working with at the time, and no matter how many times I responded to this, people just believed I must be running things. I believe this was confirmation bias at least partly based on the assumption that a Ugandan man – mbu muyaye – could not express himself so eloquently and confidently without a muzungu writing for him, which is just not true.

This thinking is a symptom of the same mindset that believes “local” is an insult, and better things must come from outside countries. Meanwhile, so many amazing creators are making Uganda proud to be local! Mindset change is so needed to deal with these injustices that rob society of development, but people’s thinking is changing mpola mpola…

So, what can I personally do to remedy my situation of benefiting from cultural and systematic injustices? Well, I think it is my responsibility to make sure to treat everyone with respect, and to listen and learn from others. If I notice that my white privilege is showing, I should take a minute and consider whether I could make another choice to help bring more equity to the situation. As for opening doors that not everyone can, once I am inside I will do the best work I possibly can to stay there and make a positive impact. When I know Ugandans who have value to offer, I will recommend them for jobs, and if my clients ever try to underpay artists, staff, entrepreneurs, etc. I will argue on the behalf of the oppressed, because we all deserve that dignity.

It’s not so easy sometimes. Honestly, privilege of any kind – whether based on your gender, class, etc. – it can mess with your head and make you think you’re a VIP. But then look down at the world from space and all us humans and our drama are even too small to see. We are nothing, or we are all VIPs.

I don’t like the word “expat,” because Ugandans in Toronto are not called expats – they’re called “immigrants” - and also it sounds too close to “expert.” We cannot deny that many white people in Uganda are paid more than their Ugandan colleagues, regardless of some migrants' inferior expertise in their roles and responsibilities.

On many occurrences, I have been waved through security checks while the Ugandan people I’m with are asked to open their bags. I actually have to say: “here, check mine too.” I often joke cynically that the biggest terrorist threat in Uganda could be a muzungu’s purse.

I have traveled a lot with my Ugandan friends around the country, and I have one friend named Nvannungi who likes to tease me with the reminder: “Anne, your White Privilege is showing!” (This blog is dedicated to you, Leadership.)

Last year, I travelled upcountry with my housemate Zalwango, and we noticed that many of the hotel staff and other service providers would look me in the eye while speaking, and pretty much ignore her. They’d offer to carry my bags and not even notice when she held out hers. I tweeted about this and was advised that I was served better in the expectation of better tips - muzungu = $$$ - never mind the reality of the situation, which was that my friend and I were splitting the cost of the trip and deserved equal service. We were both upset, not at the people themselves, but at the injustice in that way of thinking.

I have worked on so many funding proposals and pitches of different kinds with teams of Ugandans, and we noticed that when a Ugandan teammate contacts a potential partner, they are often ignored, but the name Whitehead gets a reply. I understand the lack of trust in a market that can often be too “unserious” about professionalism and integrity, and I do good work, but my muzungu name also has a more positive prejudice.

When a Ugandan welcomes a muzungu into their country, they open doors (literally and figuratively) lead you in and offer you the best seat available. They are warm and receptive. They take time to talk with you, and offer you any food or drink they have. A Ugandan will speak their very best English with a muzungu, and then praise the migrant for even one or two words in the local language that they can fumble out. A Ugandan does not expect a foreigner to learn their languages the way a Ugandan would be expected to speak English in America.

Through a confluence of a trending news cycle and my relationships in Uganda’s media – and I think some White Privilege – I found myself this past week in the middle of a story that run faster than Kiprotich. Everyone was giving me credit for PR that I wasn’t doing, calling me a “manager” of someone I wasn’t even working with at the time, and no matter how many times I responded to this, people just believed I must be running things. I believe this was confirmation bias at least partly based on the assumption that a Ugandan man – mbu muyaye – could not express himself so eloquently and confidently without a muzungu writing for him, which is just not true.

This thinking is a symptom of the same mindset that believes “local” is an insult, and better things must come from outside countries. Meanwhile, so many amazing creators are making Uganda proud to be local! Mindset change is so needed to deal with these injustices that rob society of development, but people’s thinking is changing mpola mpola…

So, what can I personally do to remedy my situation of benefiting from cultural and systematic injustices? Well, I think it is my responsibility to make sure to treat everyone with respect, and to listen and learn from others. If I notice that my white privilege is showing, I should take a minute and consider whether I could make another choice to help bring more equity to the situation. As for opening doors that not everyone can, once I am inside I will do the best work I possibly can to stay there and make a positive impact. When I know Ugandans who have value to offer, I will recommend them for jobs, and if my clients ever try to underpay artists, staff, entrepreneurs, etc. I will argue on the behalf of the oppressed, because we all deserve that dignity.

It’s not so easy sometimes. Honestly, privilege of any kind – whether based on your gender, class, etc. – it can mess with your head and make you think you’re a VIP. But then look down at the world from space and all us humans and our drama are even too small to see. We are nothing, or we are all VIPs.